CHILDREN'S FICTION cited as factual document

NO PHOTOGRAPHS of prisoners or anyone else exist by A. H. BOYD

PRISONER PHOTOGRAPHS by THOMAS J. NEVIN 1870s

The true origins of the photographic misattribution to non-photographer and Port Arthur official A. H. Boyd of Thomas J. Nevin's police mugshots of Tasmanian prisoners taken in the 1870s-1880s lies with a reference to the art historian Margaret Glover's article "Some Port Arthur Experiments" (1979) by Chris Long and/or Warwick Reeder (1995).

In 1979, Margaret Glover published an article about Port Arthur titled Some Port Arthur Experiments (In: T.H.R.A. Papers and Proceedings, vol. 26 no. 4, Dec. 1979, pp. 132-143).

The article deals with plants and animals and steam engines and the tenure of Commandant James Boyd (during the years 1853-1871). No mention is made of his successor Commandant A. H. Boyd, no mention is made of prison photography, and no mention is made in this article of A. H. Boyd's niece E.M. Hall, nor is her children's story, "The Young Explorer" (1931/1942).

Read the article by Margaret Glover (1-8)

Yet this same article by Glover and this same children's story by E.M. Hall have been cited since the 1980s by Chris Long as evidence that A.H. Boyd not only had his own photographic studio but photographed prisoners at Port Arthur in 1873 or was it 1874? Those who believe this "belief" cannot quite settle on the date - because it did not happen!

The unpublished children's "tale" in typescript form was written by Edith Mary Hall nee Giblin, a daughter of Attorney-General W.R. Giblin and niece of A.H. Boyd. It is fiction, but more than a few gullible minds believe it purports to be an account of Edith Mary's childhood visits to Port Arthur. Born in 1868, Edith Mary Hall nee Giblin, would have been no more than five years old when her uncle A. H. Boyd vacated the position of Commandant at Port Arthur in December 1873 (Walch's Tasmanian Almanac 1873; ABD online).

The root of the notion that A.H. Boyd had any skills relating to the making of photographs arose from this children's story forwarded to the Crowther Collection at the State Library of Tasmania in 1942 by its author, Edith Hall. It was NEVER published, and exists only as a typed story, called "The Young Explorer." Edith Hall claimed in an accompanying letter, dated 1942 and addressed to Dr Crowther that a man she calls the "Chief" in the story was her uncle A. H. Boyd, and that he was "always on the lookout for sitters". Hopeful Chief! The imaginative Edith and her description of a room where the child protagonist was photographed (and rewarded for it) hardly accords with a set-up for police photography. The photographing of prisoners IS NOT mentioned in either the story or the letter by Edith Hall. In the context of the whole story, only three pages in length, the reference to photography is just another in a long list of imaginative fictions (many about clothes and servants) intended to give the child reader a "taste" of old Port Arthur, when both the author and her readers by 1942 were at a considerable remove in time. Boyd is not mentioned by name in the story, yet Reeder 1995 (after Long, 1995) and Clark (2010) actually cite this piece of fiction as if it contains statements of factual information. A. H. Boyd has never been documented in newspapers or validated in any government record of the day as either an amateur or official photographer.

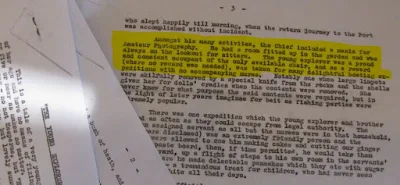

E.M. Hall. The Young Explorer, typed script courtesy SLTAS

Photo © KLW NFC 2010 ARR

Click on images for readable version

This tale has been misinterpreted as the witness account of a five year old when the fact of the matter is that it was written by a 62 year old woman in 1930 (?), submitted to the Crowther Collection (State Library) in 1942, and probably transcribed in typescript (again) at an even later date. It is a composite of general details that concord more with the imagery in the postcards sold by Albert Sergeant in the late 1880s, and Port Arthur as the premium tourist destination of the 1920s, than with the site during its operation in 1873. In short, it is FICTION.

Chris Long and Warwick Reeder wrongly assumed that Edith Hall's tale was cited in Glover's article as a true account of a "Port Arthur Experiment" by A. H. Boyd. It came to be a "belief" in A. H. Boyd as some sort of amateur photographer who only needed to press a button on a camera to be included in art photo histories as an "artist" while the REAL photographers, the professionals such as Thomas J. Nevin were just the copyists of Boyd's arty point-and-shoot prototypes (! seriously - see Tasmanian Photographers 1840-1940, 1995:36).

By 1985, the "aura" Chris Long and Warwick Reeder had spun around A. H. Boyd spread to the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, and to the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery who then created databases of their holdings of T. J. Nevin's prisoners' photographs but with Boyd's name as the "creator". By 1995, Warwick Reeder had actually cited Glover's 1979 article without checking either its contents or the children's tale written in the 1940s, and assumed that Edith Hall had written a factual account called "Reminiscences" of her childhood. Reeder thus adopted without question Chris Long's reference to Margaret Glover that "Experiments" in photography were conducted on prisoners at Port Arthur by A.H. Boyd, when Glover made no such statements.

No such "Experiments" took place: when Thomas J. Nevin was contracted by tender in mid 1872 to commence the photographing of offenders, a systematic approach was already in place which centred on the Hobart Town Goal (Campbell St) inmates, whether those incarcerated long-term, or whether those booked on arrest for a second offense, or whether those released with a TOL and other conditions. Those employed on probation in the greater Hobart region who reoffended were photographed as a priority according to the regulations adopted from the Victorian Reform of Penal Discipline 1871. So, there was no "Experiment" in prison photography conducted at Port Arthur in 1873; the numbers of the criminal class there were negligible, and those returning to the site in subsequent years until 1876 had been processed through the central Police Office in Hobart and photographed prior to their return to Port Arthur. By September 1873 Nevin had photographed 109 transferees returned from Port Arthur at the Hobart Gaol amongst a much larger number of offenders already incarcerated, in addition to those discharged (with a TOL etc) from the central police office at the Hobart Town Hall. Extant mugshots of these men (around 300) are random estrays from this much larger corpus and prisoner population.

ONCE MORE ... THE FACTS

Chris Long and Warwick Reeder began this "industry" of the A.H. Boyd attribution which has confused a generation and seriously misled the public and public institutions, even when they had no evidence to support their hypothesis; Boyd had no reputation as a photographer in his lifetime, no photographic works by him are extant, and no document exists that testifies to his training, skills in using a camera or facilities for developing and printing the final carte-de-visite which was pasted to the prisoner's rap sheet. This fictional tale by Edith Hall, delivered as a talk in 1930, and reprised by Chris Long and Warwick Reeder by the late 1980s and 1995 as a factual account, is the kernel and genesis of the myth of A. H. Boyd as an amateur photographer of convicts. In the light of police history in Tasmania, and the activities of both Thomas J. Nevin and his brother Constable John Nevin at the Hobart Gaol, such childish nonsense has to be put to rest.

T. J. Nevin's attribution as the commercial photographer and civil servant who worked with police in Hobart prisons and produced prisoner identification photographs for the Colonial Government was common knowledge in the 19th century, and firmly re-established in the 20th century through publications and exhibitions, most recently in 1977, and thereafter in 1982, 1992, 1995, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009 and 2010. Current estimates of extant examples of Nevin's "convict portraits" number more than 300 in public and private collections. These extant mugshots are estrays from a much larger corpus of over a thousand prisoner identification photographs taken by Thomas Nevin and his brother, Constable John Nevin in prisons, including the Port Arthur prison, the Supreme and City courts, and the Town Hall Municipal Police Office, Hobart between 1872 and 1886.

The only two extant photographs of Edith Mary Hall nee Giblin's father W.R. Giblin and her uncle A.H. Boyd dated to 1873-4 were taken respectively by T. J. Nevin (Archives Office Tasmania collection) and Charles A. Woolley (TMAG collection). Between 1872 and 1876, Nevin's purpose at Port Arthur was to photograph prisoners who were newly sentenced, who were being transferred back to the prison in Hobart, or who were being released with various conditions. Nevin had visited the prison at Port Arthur on several occasions, and in the company of other photographers and government contractors from the mid-1860s to its devolvement under Dr. Coverdale in 1877.

The A. H. Boyd misattribution has taken hold in the imagination of art historians who have failed to see that these extant "convict portraits" were not a fanciful one-off ethnographic portfolio (Crombie, 2004) taken by some dabbling Sunday amateur such as Boyd is portrayed (Long, 1995; Reeder 1995; Ennis 2000), but were police mugshots, taken over a decade in the usual circumstances and for the same reasons that all mugshots are taken today, and by professional photographers contracted or employed for the purpose, as were the brothers Thomas and John Nevin between 1872 and 1886.

When Warwick Reeder submitted an MA thesis (ANU) in 1995, the same date which saw the publication of Chris Long's promotion of A. H. Boyd and trivialisation of Nevin (TMAG 1995), he clearly stated that Chris Long was the first to suggest a photographer attribution of convicts to A. H. Boyd, based on Margaret Glover's article which he cites along with Edith Hall's children's tale of a five year old sister and her brother at Port Arthur. Reeder's research on Nevin adopted Chris Long's tenor and text, and his few details were extremely inaccurate and deliberately misleading. His thesis promulgated the A. H. Boyd shibboleth, displaying a breath-taking ignorance of police history in the process. .

Below: page 69 of Warwick Reeder's MA thesis (The Democratic Image, ANU 1995) which contains just three pages of relevant discussion. The error re A. H. Boyd's tenure is repeated here: he was not at Port Arthur in 1874, he had resigned from the post of Commandant by December 1873 (ADB online; Walch's Almanac 1873).

And the footnote 65: Margaret Glover's role. Reeder had not checked Glover's article, nor Edith Hall's "story". He assumes its title was "Reminiscences" i.e. written within the genre of memoirs when the actual title is "The Young Explorer" and the genre is children's fiction. Glover's article contains no mention of either E.M. Hall, A.H. Boyd, photography or prisoner photographs.

Reeder assumed that (a) A. H. Boyd ordered photographic equipment himself, although no government document shows payment of the order; (b) the equipment, specifically glass plates, actually arrived at Port Arthur, when there is evidence they did not leave Customs in Hobart; (c) these specific photographic plates were used to photograph prisoners in situ at Port Arthur, despite the evidence suggesting commercial photographers Clifford & Nevin were on site in 1873-74 for the purpose of photographing the buildings, the surrounds, and visiting dignitaries, and that Nevin was there again in May 1874 working with Dr. Coverdale (d) and that Boyd took the photographs himself, again despite a complete lack of evidence that he ever held a camera, let alone used one for official records. The so-called "room" set up as a studio is an archaeological fiction now in print as a full-blown fantasy (Clark, JACHS 2010). There was originally a building constructed in 1865, by an earlier official, Commandant James Boyd (presumed to be no relative of A. H. Boyd) as the Literary Institute for officers and families, of which James Boyd was the founder and president. By the 1890s, this "room" or any of the others constructed by James Boyd may well have functioned as a place where tourists were photographed by postcard producers such as Albert Sergeant and E. Little into the 1890s, but there was never a place constructed by A.H. Boyd as a photographic studio designated for the production of prisoner mugshots in 1874.

Warwick Reeder's account of his efforts to fully research the involvement of A. H. Boyd contains the often repeated phrase that by 1995, there was just ONE prisoner photograph held at the QVMAG Launceston (among 112) bearing T. J. Nevin's (government) stamp on verso. But previous researchers at the QVMAG maintained there were quite a few, in addition to photographs by Nevin of commercial products, trader's advertisements, and private clientele (John McPhee, curator of Nevin's CONVICTS Exhibition at the QVMAG, 1977; Chris Long, letter to Nevin descendants 1984). Many more convict cdv's have surfaced with Nevin's stamp, and some of these stamped items were "removed" from the public collection between 1977 and 1995 (by whom? Long indicated in an email to Nevin descendants in 2003 that he had a lot more on Nevin in boxes in his garage which never made it past his editor Gillian Winter, TMAG 1995). One album of prisoner cdvs had found its way to the National Gallery of Victoria (McPhee, verbal communication 1986), accessioned at the National Library of Australia in Thomas Nevin's name by 1982 (see the NLA's accession records), and misattributed to A. H. Boyd under Long and Reeder's influence in two instances (In a New Light online exhibition 2003; Clark "essay" 2007).

There is of course the assumption, ingrained in the art historian's psyche, that a photographer's stamp proves authorship. Yet the Mitchell Library SLNSW which also holds a collection of Nevin's prisoner photographs, had been influenced enough by Long and Reeder's determination not to let it go that they placed a catalogue note next to the two prisoner photographs which are printed verso with Nevin's government contractor Royal Arms colonial warrant stamp, suggesting Boyd took the originals (SLNSW, PXB 274). Boyd's name has since been removed. It is perversity to ignore the photographer's stamp in matters of attribution; but it is corruption which seriously prefers in lieu an attribution based on a paragraph in a children's story.

The majority of T. J. Nevin's prisoner mugshots were reprinted in duplicate and even hand-tinted for heightened realism, and for reasons to do with informing the public at large of criminals wanted on warrant during the 1870s and 1880s. Nevin was the only photographer in Hobart over the decade from 1873 to use a stamp which incorporated the Hobart Supreme Court's insignia of lion and unicorn rampant, the Royal Arms, signifying joint copyright under tender to the government. One photograph per batch (of 100) was required for copyright registration. Printing a stamp verso was unnecessary on his later prisoner mugshots which were taken exclusively within and for the prison administration once he became a full-time civil servant.

Below: Warwick Reeder's highly inaccurate information (1995) about Thomas J. Nevin: by 1888 Nevin was the father of seven children (six survived), not two. He did not cease photography in 1876, he ceased commercial photography temporarily to work full time as Hall Keeper for the Hobart City Corporation and police photographer with the Municipal Police at the Town Hall and Hobart Gaol with his brother Constable John Nevin. At the Town Hall he was also the Office Keeper (a position title denoting manager of an archive still in use at the Archives Office of Victoria). Reeder not once countenanced the existence of a police photographer in Hobart producing these mugshots, nor did he reference the work of earlier prison photographers Frazer Crawford (1867, SA) and Charles Nettleton (1874 onwards in Vic). Reeder fusses about the museological history of the photographs in this short thesis. Sadly, it is this solipsistic and self-referential preoccupation that prevents Reeder (and others in his profession) from adding real value to the history of the national heritage because they have pursued a parasitic attribution which leads to a dead-end. Establishing the plain facts about the jobbing photographer Thomas J. Nevin going about his work and supporting his large family should have been his starting point, joining the photographer on the ground, at ground zero, carrying out the daily routine with the police.

NB: do NOT quote or cite these excerpts (at Reeder's request)

Below: The Young Explorer (1931), by Boyd's niece Edith Mary Hall, the fictional story for children about a "Chief", i.e. the Commandant at Port Arthur which has been misinterpreted as evidence that A.H. Boyd photographed prisoners. In reality it was Edith Hall's father, W .R. Giblin, and not her uncle A.H. Boyd, who was keenly interested in the judicial uses of photography. Giblin was Nevin's family solicitor by 1868, neighbour at Kangaroo Valley, and referee for membership of the Australian and International Order of Odd Fellows Lodge and civil service with the HCC.

Below: Edith Mary Hall, born 1868 (Archives Office of Tasmania), daughter of Nevin's family solicitor and referee, Attorney-General William Robert Giblin:

Below: Margaret Glover (1979), Some Port Arthur Experiments, the publication which has been cited as evidence in support of an A.H. Boyd "attribution" as a photographer who took photographs of convicts as an "experiment". Glover's article contains nothing about A. H. Boyd, nothing about E.M. Hall and nothing about photography. In May 2010, Clark recast Glover's word "Experiment" into the idea that Boyd set himself a "project"- a new word for a passé deception. (JACHS 2010:83).

The A.H. Boyd misattribution has wasted the time and effort of a generation with an interest in forensic and police photography and will continue to do so until the gatekeepers of Nevin's prisoner photographs in public collections countenance the fact that fiction is not fact and that T. J. Nevin's legacy is extensive within the historical contexts of police photography in Tasmania.

RELATED POSTS main weblog

- Convict cartes by Thomas Nevin at the new National Portrait Gallery

- "In a New Light": NLA exhibition with Boyd misattribution

- Professor Joan Kerr (DAA ed. 1992)

- Prison photographers Nevin, Nettleton & Crawford

- ‘Tasmanian Photographers 1840-1940: A Directory’ (TMAG 1995)

- Two histories, two inscriptions (TMAG 1995)

- Anne-Marie Willis & Richard Neville on the A.H. Boyd misattribution

- The QVMAG, Chris Long and the A.H. Boyd misattribution

- Helen Ennis’ NLA publication ‘Intersections’ 2004

- Isobel Crombie and Helen Ennis: how misattribution can persist

- The A.H. Boyd misattribution at DAAO

- A Question of Stupidity & the NLA